Introduction: The Price Looks Right, But Something’s Off

You’ve seen it before. A stock trading at 6 times earnings. Or maybe it’s below book value. On paper, it screams “bargain.” But months later, it’s still stuck—or worse, it’s fallen even more. You wonder, what did I miss?

This article will help you avoid one of the most costly mistakes in value investing—falling into a value trap. We’ll unpack what it is, how it lures in smart investors, and how to tell the difference between a true bargain and a dead-end. Because when you learn to sidestep these traps, you stop bleeding money on mirages—and start compounding real wealth.

What Is a Value Trap?

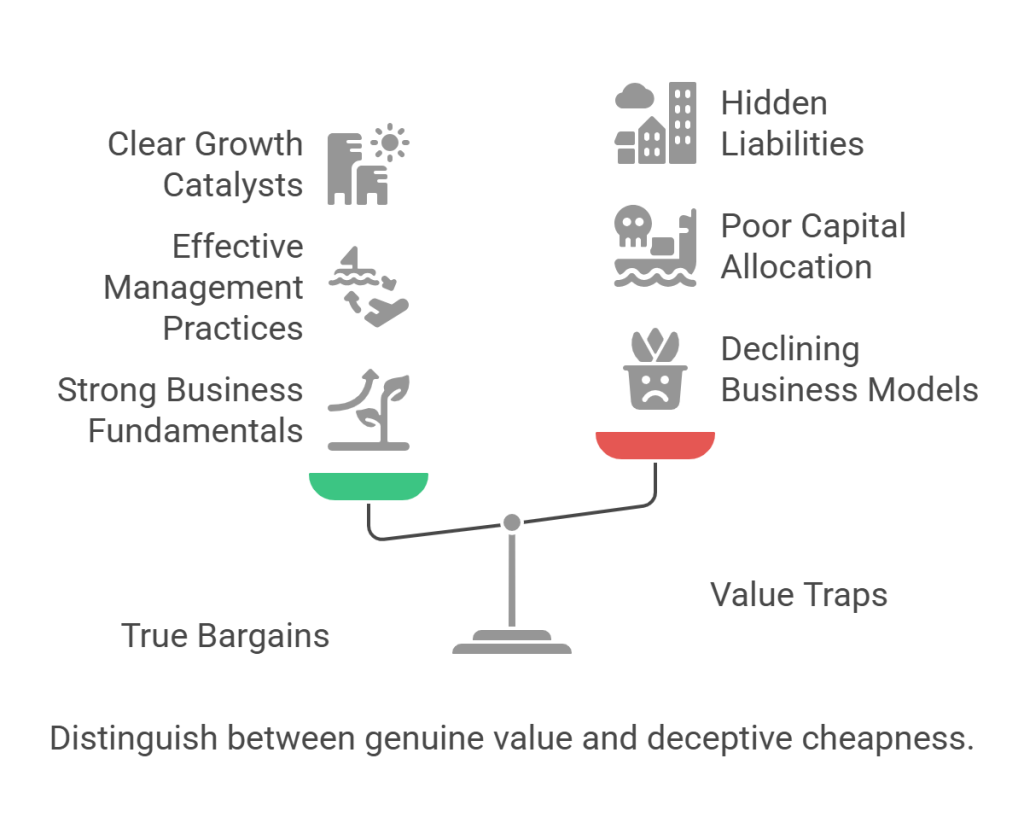

Let’s define it clearly before we diagnose it. A value trap is a stock that appears cheap by traditional valuation metrics like P/E or P/B—but is actually fairly priced or even overpriced once the underlying business risks are accounted for.

In other words, the stock is not undervalued—it’s just cheap for a reason. And that reason is often hiding in plain sight.

Why Value Traps Are So Tempting

This is where things get tricky. Value traps wear the right clothing. They look like your favorite Ben Graham-style opportunities—low multiples, strong balance sheets, maybe even a dividend. The screeners flag them. The charts support them. But the market’s not stupid. There’s usually a deeper problem the numbers don’t reveal at first glance.

As a value investor, your edge comes not from buying what looks cheap—but from knowing what’s truly mispriced. And value traps are designed to fool exactly the kind of investor you aspire to be.

Common Causes of a Value Trap

Understanding the anatomy of a trap is your first defense. Here are the most frequent culprits:

Declining Business Models

A classic trap. The company is profitable today but competes in a shrinking industry with no future. Think landline telecom, print media, or legacy retailers stuck in the past.

Poor Capital Allocation and Management

A business can look cheap on the surface, but if management is consistently lighting capital on fire—buybacks at the wrong time, unprofitable acquisitions, debt-fueled growth—you’re looking at a permanent impairment of value.

No Catalyst

Without a clear and plausible reason for the stock to re-rate—activist involvement, asset sale, turnaround plan, or industry tailwind—cheap can stay cheap forever.

Cyclical Risks Masquerading as Stability

Some businesses are highly cyclical, but the downcycle hasn’t hit yet. This creates a false sense of stability, and by the time earnings collapse, the “value” was just a mirage.

Hidden Liabilities or Off-Balance Sheet Risks

Pensions, environmental liabilities, or opaque financial structures can undermine the value case once you dig deeper. Always go beyond the income statement.

How to Spot a Value Trap Before It’s Too Late

Here’s where your process makes all the difference. To separate the wheat from the weeds:

Look beyond the multiples. Start with P/E and P/B, but don’t stop there. Dive into the cash flow statement, working capital, and debt structure.

Check for catalysts. What will make the market wake up and reprice the stock? If the answer is “nothing,” be cautious.

Evaluate the moat and management. If the moat is eroding or management is asleep at the wheel, your margin of safety is illusory.

Watch out for low-quality earnings. One-time gains, accounting games, or aggressive assumptions can mask deeper weaknesses.

Ask why it’s cheap. Always. And don’t accept “the market is wrong” as an answer without a specific, data-backed reason why.

To go even deeper, make use of advanced metrics that paint a fuller picture:

- Piotroski F-Score: A composite score based on nine criteria measuring profitability, leverage, liquidity, and operational efficiency. Low scores often signal weak financials masked by cheap multiples.

- Free Cash Flow Yield: This tells you how much actual cash the business generates relative to its price. Low earnings with strong FCF may indicate conservative accounting—or vice versa.

- Return on Invested Capital (ROIC): High ROIC is a sign that the company uses capital efficiently. A stock trading at a discount but generating poor returns on capital is waving a red flag.

- DuPont Analysis: Breaks ROE into its component parts—profit margin, asset turnover, and equity multiplier—helping you understand if a high ROE is driven by genuine profitability or excessive leverage.

These metrics give you a framework to separate statistical cheapness from true intrinsic value.

Real-Life Example: The Trap That Burned Even the Best

In the early 2010s, many value investors were drawn to RadioShack. It had low multiples, name recognition, and an asset-heavy balance sheet. But the business was being eaten alive by changing consumer behavior and competition. Consumers were shifting to online shopping, and the types of products RadioShack specialized in—cables, batteries, and small electronics—were becoming increasingly commoditized and easily available elsewhere.

Unlike Best Buy, which pivoted aggressively to become a trusted showroom for major electronics brands and embraced price-matching and improved customer experience, RadioShack clung to a shrinking niche and failed to redefine its relevance. The turnaround never came. It wasn’t undervalued. It was in decline—and that’s a different game entirely.

What to Do If You Already Own a Value Trap

Don’t double down on hope. Re-evaluate your thesis ruthlessly. Has the intrinsic value changed? Has the catalyst failed to materialize? Are there better uses for your capital?

One rule that has served me well is this: if a stock hasn’t performed for two years, it’s time to exit. This doesn’t mean the idea was wrong, but capital tied up with no return is capital that can’t be deployed elsewhere. Opportunity cost is real, and over time, it can erode your long-term performance as much as actual losses.

Cutting losers isn’t weakness. It’s the hallmark of a disciplined investor who knows when to move on.

Turn Traps Into Triumphs

The truth is, every value investor will fall into a trap at some point. What separates the amateurs from the pros is how quickly they recognize the mistake—and how they adjust going forward.

If you have sufficient capital—or can rally enough like-minded shareholders—you might even mount a shareholder action: replace management, gain a board seat, or push for a strategic review. These are real levers to unlock value when the business isn’t moving on its own. But let’s be honest: for most retail investors, this is easier said than done. Without scale, you’re relying on patience and price to work things out.

The best investors in the world are relentless about one thing: protecting their downside. Because when you remove the downside, all that’s left is the upside.

Final Thoughts: Don’t Just Buy Cheap. Buy Smart.

A stock isn’t a bargain just because it looks cheap. It’s a bargain if its future cash flows, discounted back to the present, give you a clear margin of safety with real upside.

If you build your portfolio with this discipline, you won’t just avoid value traps—you’ll turn your capital into a long-term compounding machine.

And that’s how real wealth is built.

Shailesh Kumar, MBA is the founder of Astute Investor’s Calculus, where he shares high-conviction small-cap value ideas, stock reports, and investing strategies. He is also a strategy and operations consultant focused on measurable business outcomes

His work has been featured in the New York Times and profiled on Wikipedia. He previously ran Value Stock Guide, one of the earliest value investing platforms online.

Subscribe to the Inner Circle to access premium stock reports and strategy insights.

Featured in: